Oysters on the half shell, the willingness to savor this gastronomic treat that I inherited from my parents. The slippery, mildly briny, sometimes sweet oyster, swallowed with a squeeze of lemon or a dollop of pungent, fresh horseradish is something I relish at the local shellfish bar. I have never eaten raw oysters with my parents, but knew they enjoyed the delicacy, until being succumbed by Hepatitis A in June 1974 with tainted east coast bivalves. That summer was BORING being isolated on our family’s one-acre wooded, suburban lot, as my parents recovered from being exhausted by their jaundiced liver disease.

Since 1992, a Hepatitis A vaccination has been available to ward off the infection, as the disease can be contracted worldwide from water polluted by untreated sewage which is used for washing fresh produce, drinking water, or discharged to shellfish beds. What if, rather than protecting ourselves by vaccination, our worldwide priority was to keep our estuaries, rivers, creeks, and drinking water sources clean and uncontaminated?

Local Northwest Shellfish

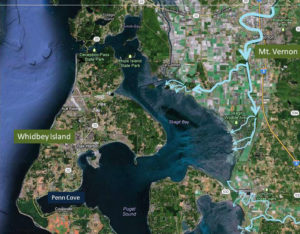

Penn Cove, a quiet, mostly rural inlet in Puget Sound with the 1,850 resident Coupeville metropolis on its southern shores, is on the east side of Whidbey Island and is home to Penn Cove Shellfish, LLC, the largest mussel producer in the United States and a significant distributor of Manila Clams, Kumamoto oysters and 30 varieties of Pacific oysters. The Jeffords family established the company 28 years ago, creating a truly sustainable, premium shellfish operation. Orders received at command central by 11 a.m. Pacific time, are shipped world-wide and received at their final destination within 24 hours of being plucked from the sea.

The Skagit and Stilliguamish Rivers routes that feed Skagit Bay and Penn Cove

On a brisk, but sunny March day, I savored a Kusshi–a tray raised Pacific oyster with a delicate, sweet flavor, a Baynes Sound–a tray-raised and beach hardened larger Pacific oyster with a bit too much brine for my taste, and a Kumamoto–its own species served with the Philadelphia flip allowing the oyster to be drenched in its natural juices, raised on longlines in the cool Pacific waters with just the right amount of oyster flavor and a mild fruity finish. Just as there is a terroir, or differentiation in flavor, color, size or other characteristic of a land-based crop because of its growing conditions, the vast majority of Crassostrea gigas, more commonly known as Pacific oysters, develop their size and flavor based on their home marine environment. An oyster’s aquatic dining table is dependent not only on the health of its immediate surroundings, but also on upland conditions. Penn Cove Shellfish staff monitor the water quality regularly ensuring that only the freshest water from Puget Sound and the Skagit and Stilliguamish Rivers are feeding these critters. Clean storm water runoff, uncontaminated discharges from sewage treatment plants, and controlled and metered application of agricultural fertilizers are critical to conveying fresh water suitable for raising bivalves in Penn Cove.

I swallowed my shellfish with unimpeded joy knowing they are one of the lowest animals on the food chain, rated as “Best Choice” by the Monterey Bay Seafood Watch Green List, and the freshest I could get.

Oyster Capital of the World

Today, a quick internet search of the “oyster capital of the world” flags Long Beach, South Bend, and Willapa Bay, Washington, all northwest breeding grounds for bivalve farming as receiving this moniker. Mussel, clam, and oyster cultivation is prevalent all along the west coast with the largest concentration of businesses in Washington, putting it on track to become the nation’s largest shellfish supplier as the number one and two locations in the United States, Chesapeake Bay and Gulf of Mexico, harvests sizes are decreasing.

Just 130 years ago, it is astounding to think that “New York (City) was the undisputed capital of history’s greatest oyster boom,” according to Mark Kurlansky in The Big Oyster, History on the Half-Shell. Beginning with the Dutch settlement in 1613 in what is now known as the Big Apple, New Yorkers feasted on locally-harvested oysters and shipped them to international markets from Arthur Kill, Staten Island, and Jamaica Bay, Long Island, now home to the John F. Kennedy International Airport. By 1930, all of the commercial oyster beds in the New York metropolitan area were shuttered from dirty, silty, storm water runoff, thousands of pounds of heavy metal industrial wastes entering the marine environment via sewage system discharge points daily, and sewage sludge being dumped only 12 miles out to sea, which was not far enough away to prevent impact to the shellfish beds. Oysters cannot and did not survive this harsh, industrialized environment.

Today, few people remember tasting a New York Harbor raised oyster. The demise of the New York world-class oyster business should serve as a reminder to remain vigilant about protecting our Puget Sound water resources and concurrently our marine habitat and shellfish industries, as oysters truly are an indicator species. Thankfully here in Washington, we are years away from needing a Hepatitis A vaccination to protect ourselves from locally infected shellfish or drinking water and only need it when we travel outside the country to places where water quality standards are lax. My mother, after a 39-year hiatus, is even considering slipping a Washington grown oyster with a dab of cocktail sauce down her throat on her next west coast visit.

Kathryn Gardow, P.E., local food advocate, a land use expert and owner of Gardow Consulting, an organization dedicated to providing multidisciplinary solutions to building sustainable communities. Kathryn has expertise in project management, planning, and civil engineering, with an emphasis on creating communities that include food production. Kathryn’s blog will muse on ways to create a more sustainable world.

I love oysters, too and the East Coast oyster is still pretty lovable.

Oyster Friend (Bryan)