Fulton County, Georgia is best known as the home of Atlanta, the 9th most populous U.S. metropolian area and Hartfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the most traveled U.S. airport. North of downtown Atlanta is continuous suburbs, countless dead-ends and endless strip malls. At the south end of Fulton County, no more than a 30-minute drive from downtown is Chatahoochee Hills an incorporated city with less than one percent of the County’s population and about 10% of the County’s land area. Chatahoochee Hills is predominately rural with rolling hills, pastures, and woods. Just over ten years ago, this city protected itself from the bane of traditional suburban real estate patterns by incorporating 32,000 acres of rural lands into a municipal city and developed a plan to house just as many people as north county, but not in the same way.

Incorporation was accomplished by following a rigorous land use planning process with community meetings and political will that challenged land use patterns of classic American suburban sprawl. One leader of this land use decision process was Steve Nygren, who had moved with his family into south county in the early 1990’s and purchased 1,000 acres. Steve, a former restaurant owner turned developer knew that south Fulton County did not have to be destined to grow into classic American slurb. Now in the heart of Chatahooche Hills, Serenbe a New Urbanism development is the brainchild of Steve’s.

Walking Paths & Constructed Swales

Visiting Serenbe in April 2014 on a tour organized by the American Planning Association, I was energized seeing a community that was forward thinking rather than just the norm. As a professional civil engineer, I have designed subdivisions and reviewed development projects on behalf of jurisdictions for much of my career. At Serenbe, traditional land use planning and public works infrastructure standards have been challenged and eliminated, creating a master planned development community that works with the natural environment bringing comfort and joy to the residents rather than the incessant drone of the suburbia.

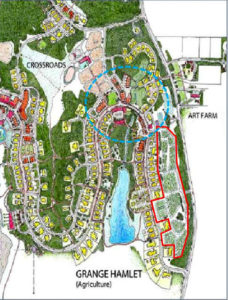

There are currently three hamlets or town centers at Serenbe with a fourth proposed, each having a different community focus. Selbourne Hamlet focuses on the arts, Grange Hamlet is a farm and craft community, and Mado Hamlet centers on health and well-being and is also the location of the adult active development. A fourth hamlet is proposed with emphasis on education. On our visit we toured Selbourne and Grange Hamlets.

Let me give just two examples of why Serenbe was attractive and excited me. One from my perspective as a civil engineer and the other from my passion on integrating food production into residential developments.

Challenging Public Works Standards

Fenced Retention Pond in Seattle Suburbs

Typical subdivision roads are designed to accommodate parking, a five-foot sidewalk, and two-way traffic flow and of course, the largest fire truck the district owns. These requirements demand a minimum 48-foot pavement width. If the neighborhood is lucky, there could be two five-foot sidewalks on each side of the road, requiring a 60-foot wide publically-owned right-of-way. In typical engineering design, the road section from curb to curb is always crowned with a high point in the middle so stormwater can flow to the street sides to be piped away to a detention facility. This facility is designed to store excess stormwater during large storms and then slowly release the water back into the natural creek or wetland system, thereby reducing the chances of unwanted flooding or scouring. Sometimes the system is designed as a retention system with a small permanent pond at the bottom, but too often, it is a large empty hole in the ground surrounded by a fence.

Typical Subdivision Grading

House lots are typically graded such that the homes face each other, are not offset, and are at the same elevation across the street from each other. It is a very regular, predictable pattern. Because most developable land is no longer flat, mass earth movement and tree removal is necessary to create flat housing lots with retaining walls between the side or backyards to accommodate any grade differentiation. Houses step down as a subdivision road descends, hence engineering a fit rather than designing with the natural environment.

For more than 20 years mass grading and fenced in storm ponds have been standard engineering practice to managing stormwater and designing house lots. Designers at Serenbe turned this typical engineering subdivision model on its head. Steve spoke with passion about fighting against the standards with the Public Works Department to create a community that works with the natural site topography and for the people.

Serenbe Community Map

The roads are designed with hairpin curves, typical for mountain passes and not housing developments, that slow down traffic and cater to people walking rather than just cars driving. (An hairpin curve is circled in blue on the map.) This innovative road design creates wooded backyards for lots on the inside of the curve and at the same time a place to direct stormwater for biofiltration. Walking on the forest paths between the homes my engineering eye could see where the water flows. At the same time my childhood memories recreated stories of “playing house” in the woods, scraping forest floor leaves into long piles for pretend walls. Mixing mushrooms, berries, and leaves together to create a “scrumptious lunch,” eaten in the “dining room” built from downed logs. Every Serenbe kid has the chance to create their own fantasy house in their backyard!

Back at the street, the lots are designed to work with the topography, with some houses actually lower than the road, creating the feel that the community has been around for a long time. Pavement widths are no more than 40-foot curb to curb when parking is provided and shrink to 24-feet wide when only a two-direction traveled way is needed. Pavement edges are defined by granite curbing, which was no longer permitted by the road standards, but establishes a quality of a bygone era. Sidewalks are found close to the center of each hamlet and forest paths connect the community in the backyards.

Selbourne Hamlet is built for people–children, adults, and the elderly–not just for cars, creating peace and calm.

A Farm at Serenbe

Homes in Grange Hamlet

Serenbe Farms is located in Grange Hamlet, integrating food growing with residential living. In most of America, food just shows up, whether in a grocery store or restaurant. As Americans, we take food for granted and forget that it actually grows in real dirt, by an actual person that plants, tends, and harvests it. Someone then cleans, packages, and transports it to a place where we purchase a farmer’s hard work. For most, this connection to food growing is forgotten. At Serenbe the link between food growing and eating is made real.

In Grange Hamlet, 25-acres are dedicated to organic agriculture and is the backyard for a street of homes. (The farm is outlined in red on the Serenbe map.) Serenbe Farms is a teaching or incubator farm, where interns learn the food growing trade and eventually move on to their own land to practice their profession. Only eight acres are currently cultivated producing 60,000 pounds of food annually that support a thriving Community Supported Agriculture program, the Serenbe neighborhood farmers market and chefs both at Serenbe and in metropolitan Atlanta. This connection to food and its cultivation reunites us with the basic necessities of life–EATING!

At Serenbe, I was infused with serenity of place and at the same time energized by innovation in community building.

Steve Nygren is creating a multi-generational community for families with children, retirees, and anyone else that wants to be connected to the essentials of living. Eating good food, playing in nature, walking in the woods, and enjoying the arts are all found at Serenbe. Alas, the price point for purchasing a home serves only an affluent clientele. Even so, the subdivision design elements and integrating the community with nature and food production are important to consider in future development projects. Rather than designing for the automobile, Serenbe is a stellar example of a community for people.

Kathryn Gardow, P.E., is a local food advocate, land use expert and owner of Gardow Consulting, LLC, an organization dedicated to providing multidisciplinary solutions to building sustainable communities. Kathryn has expertise in project management, planning, fundraising, and civil engineering, with an emphasis on creating communities that include food production. Kathryn is a Washington Sustainable Food and Farming Network board member and on the Urban Land Institute–Northwest District Council’s Center for Sustainable Leadership planning team. Kathryn’s blog muses on ways to create a more sustainable world and good food!