I was born before trucking in out-of-season foods was the norm. Most of the year our usual nightly dinner veggie was frozen (not canned) beans, peas, or vegetable medley with meat and potatoes and the iceberg lettuce wedge. Mid-winter fresh produce included a plethora of oranges and grapefruits from California or Florida or Texas. When summer’s farm grown abundance finally arrived our dinners changed dramatically from the drab iceberg lettuce salads to the myriad of textures, flavors, and robust freshness of so many locally grown foods. Growing up in Connecticut we devoured locally grown and produced foods with the seasons.

Dad made regular evening stops on his way home from work at Wade’s Farmstand** in the Connecticut River Valley before traveling over the “mountain.” Dad purchased the freshest radishes, cucumbers, blueberries, strawberries, melons, and corn! The silken ears were freshly picked every morning, as heritage corn-on-the-cob varieties lose their sweetness with each passing hour turning the flavor to pasty starch. The strawberries burst with flavor to be slurped. Radishes, coming in rounds, spikes, and as big as carrots with colors varying from bright red to white and every shade in between, smacked with sharpness. Melons ranged from smooth to rough skin with red, orange, and green inside.

Hot humid summer days, moved into crisp, clear fall days with abundant apple varieties. McCouns graced the farmstand table for what always felt like such a short time, while McIntosh being storage apples were available until spring. Pears, peaches, plums all thrived in the Farmington River Valley at a slightly higher elevation, upstream from its confluence with the Connecticut River.

At home, Dad had a penchant for the ripest, most delectable tomatoes, growing upwards of 20 different plants, including cherries, beef steaks, and early and late varieties just for the optimal burger tomato, a plate of tomatoes with chives, or to just pop in the mouth. Dad’s love of good, locally grown fruits and veggies inspired me to plant my first garden as a teenager. My first crop–Blue Lake bush beans–two bites of crisp, succulent, flavorful goodness. Now, I plant Blue Lake pole beans to use my city lot’s garden space more economically.

Seed Evolution

As a young person, unbeknownst to me our seed supply and hence our abundant produce diversity was shrinking. Large scale corporately owned agriculture often known as “Big Ag” was homogenizing and limiting fruit and vegetable choices with the mantra of efficiency and cost savings. Working with Big Ag were faculty and graduate students research scientists, funded by large corporate companies at the nation’s big agricultural schools, developing seed stock with characteristics favoring pest resistance, optimizing color, generating uniform size, and insuring travel durability. With Americans busier and more dependent on the grocery stores or now today grocery home delivery, the expectation of flawlessly shaped, perfectly colored, unblemished, pest-free fruits and vegetables became the expected standard. Shoppers did not take the extra time to visit the local farmstand and often shunned the more flavorful produce as it could be misshapen or deteriorate quickly as it was not bred for long term storage. Eaters were retrained to shop for food with their eyes for shape and color, rather than with their taste buds. These changes impacted the seed stock.

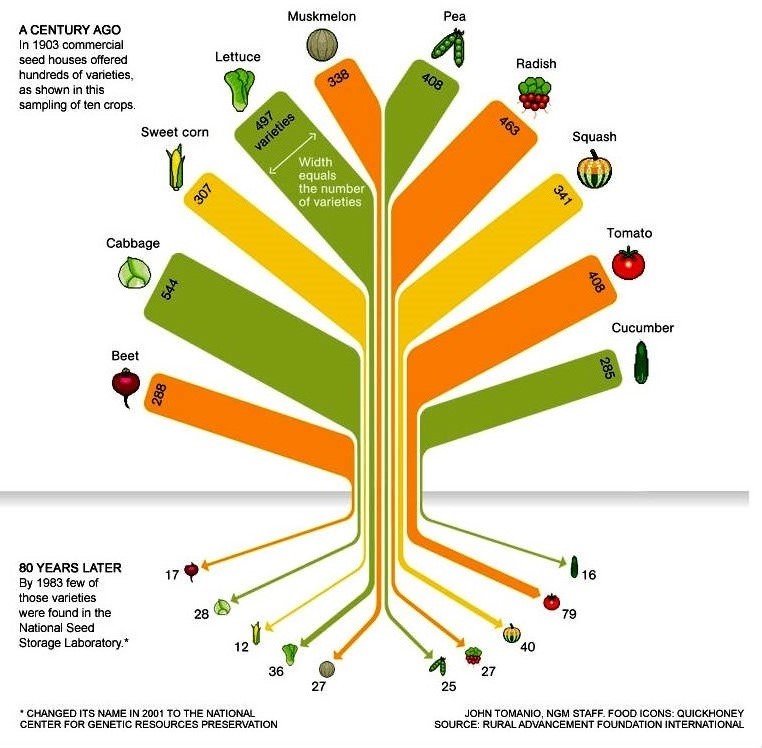

Produce variety loss is real. In 1903, there were 544 different types of cabbage seed and 80 years later there were only 28, a 95% drop in seed variety as shown on the graphic created by RAFI-USA (Rural Advancement Foundation International) a non-profit dedicated to sustainable farming and farming families. Seed selection plummeted by more than 90% for all crops except for squash which fell 88% and tomato varieties which only decreased by 81%! (The RAFI illustration was created from data available with the United States’ National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation (NCGRP) [formerly known as the National Seed Storage Laboratory], located in Fort Collins, Colorado.) This is a significant loss in seed variety. As every high school student learns in their first biology class, diversity of a species is critical to survival of the species. The precipitous decline in crop variety is detrimental to the robustness and resiliency of our food system. If a bushel of corn were delicately balanced on the top of the graph, the spindly legs of the seed stock would crumble.

Seed Variety!

Skagit Valley, Washington, is a hot bed of agricultural innovation and creativity. When tenured Washington State University (“WSU”) Dr. Stephen Jones was asked to study wheat varieties in his eastern Washington home, he relocated to Skagit County a more varied agricultural landscape that once supported wheat production before the commoditization of agriculture. Dr. Jones is now Director of the WSU Breadlab in Burlington, Washington, where he and his graduate students breed wheat and other grains that are intended to be grown on small farms in the maritime West and other smaller lesser known grain growing regions in the country—-in other words not in Eastern Washington nor in the Great Plain states. Small scale grain growing once was the norm in Western Washington.

Today there is a resurgence in growing multiple heritage grains in the Skagit River basin and on the Olympic Peninsula. The grains produce flour varieties for artisan bread makers, the home baker, fledgling spirits and beer entrepreneurs, and are a benefit to the overall agricultural ecosystem in the crop rotation sequence. Grains have deep roots, about the same depth as the stem and grain head, which aerate and return organic matter to the soil.

The Breadlab is the home to a large collection of grain seeds, a King Arthur Flour Baking School-Washington, and a plant breeding and research center to ensure long term health and economic viability of grains in the Skagit ecosystem. This synergistic grain community has fostered an entrepreneurial ethos with Cairnspring Mills, Fairhaven Mills, Skagit Valley Malting, and the Bread Farm. During COVID, the Bread Farm website is updated at 7 a.m. with that day’s bakery selections of artisan breads, pastries, and cookies that sell out every day. If you are planning a day hike to Blanchard Mountain, you don’t want to miss the Bread Farm!

By purchasing locally grown food, we are supporting our friends and neighbors plus ensuring a resilient, tasty food system. Wherever one lives, whether in Connecticut or Washington or anywhere in between, there are local farmers. Buy from your farmer whether at a farmers market, a farmstand, or at the local grocery store that supports the local food economy. Local food just tastes great!

**I am happy to see that Wade’s Farmstand is still located on Simsbury Road 100 years after its founding, as you drive west out of the Connecticut Valley with the motto, “I don’t try to sell anything in my stand that I wouldn’t want to eat myself. I’ve found that the consumer will come back to the stand only if you give him top quality.”