Farming seems so idyllic. Old McDonald, the proverbial song, is my first recollection of the quintessential farming dream. A happy song with joyful animals. Seared in my memory are daytrips to my Grandmother’s house to find the choicest Halloween pumpkin; the tallest, greenest, Christmas tree, or to pick the most succulent, prized bucket of strawberries.

My Grandparents’ Farm

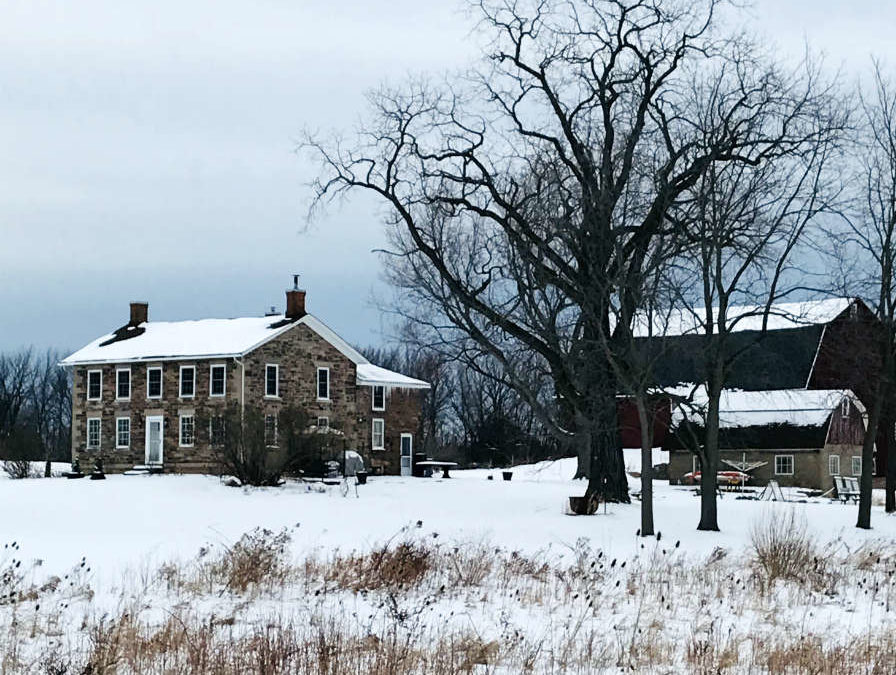

My grandparents are now long gone, but their idyllic 90-acre farm still straddles the Niagara Escarpment–the geological formation that created Niagara Falls. Half the farm, on the downhill side of the Escarpment, has poor drainage but is classified by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “prime farmland, if drained”. The uphill side, also “prime farmland,” is much drier and home to the house, barn, and garage. The wooded, steep Escarpment separating the two farming areas shelters an old quarry that was excavated beginning in the 1830’s to build the main house. As a kid, the nooks and crannies and hiding places of the huge barn, the big house, and acres and acres of land were the things that make childhood memories special.

Several miles west of my grandparents’ place, on the edge of the Escarpment, was their Christian country church. The wood-framed, two story white church with a squat steeple stood at a crossroads in the middle of farm country. There was and still is no 7-11 or gas station next door. From its perch on the Escarpment, congregants could take in the view of the flatlands to the north–all farmland. The church was a haven and a mainstay for the farming community drawing churchgoers from miles around for a weekly day of rest.

Family photo at Grandma’s memorial service

Grandma was a church regular. She was pragmatically spiritual and very community-minded. She definitely lived the mantra of how she could contribute to make people’s lives better, not just her own or her family’s, but the greater good. When we visited, our Sunday School ritual was being read a Bible verse with an accompanying lesson on being good, accepting and helping others, and finding love in our hearts. Of course there was always cutting and pasting to keep us kids occupied, too! Grandma often taught the adult class, which unfortunately, I never attended. Even so our many conversations delved into the realm of pragmatic spirituality.

Grandpa was an aeronautical engineer, entering the profession in its burgeoning days as a young techie in the 1930’s when the creative opportunities in the nascent industry were boundless. Being on the forefront of a brand new industry energized him. It tapped his creative and problem solving genes. He was a classic introvert, needing acres of space to recharge daily. He owned a tractor to mow the large acreage lawn sparsely dotted with fruit and nut trees. A hobby apiary was tucked behind the barn on the edge of the Escarpment. Grandpa would don his white uniform and bee hat regularly to tend his hives. We were never asked to help tend the bees.

The majority of Grandpa’s farmable ground was leased to a hay and corn farmer. Crops were rotated between the different fields. Since the land was Grandpa’s refuge, any crops that required daily tending by a tenant farmer were not grown. The energy to interact with other people was saved for Grandpa’s day job as an airplane wing engineer.

As with my grandparents, the neighbors and fellow churchgoers all had a relationship to the land. One memory really stands out.

The Small Family Farmer in the ’60’s

Grandma’s House & Grandpa’s Barn

The Nelsons were fellow churchgoers–a family of six, two parents and four children–just like my family. Our whole family was invited to their house for lunch after church. The Nelsons were small-scale dairy farmers with maybe a 30 to 50-head herd. Honestly, I don’t really remember the exact herd size, but the feeling of their house, the farm, and size of the operation is vivid. I know it was not a large farm. The standard clapboard house at one time blue had faded to a blue-gray and was flaking. The inside was minimally furnished with old furniture but comfortable. The property was dank and muddy and the barn looked dilapidated. As with many farmers then and now, the Nelsons were dependent on selling their product to a wholesaler at a set price. There was no ability to negotiate a higher price to cover costs, upgrade equipment, or maintain a reasonable standard of living. Even so, I do remember family being cheerful and welcoming. Still, even as a nine years old, I knew the Nelsons were poor.

In the late 1960’s our family was living frugally as my Dad was a full-time mechanical engineering PhD student. My mom stayed home with four kids. I was oldest and my only brother a toddler. My small wardrobe was mostly hand-me-downs from my younger sister, as she was already bigger than I, and a special dress sewn by Grandma. After me, the hand-me-downs were given to the Nelson girls as my youngest sister was five years younger than I. There was no reason to keep used clothing for five years until my sister grew into them. At that young age, I just knew we would never be as poor as the Nelsons. I lived in a family of possibility and opportunity. Every year my great-grandparents and later my grandparents sent birthday and holiday checks, to be put dutifully in the bank for my college education. I was expected to go to college, as both my parents and my Mom’s parents had. I knew I had options and the possibility of being comfortable and always having enough.

Supporting Small Family Farmers

Selecting the Christmas Tree

How do these memories fit into my life now? In my political, food and farming, and justice work, I often think of the Nelsons. They were living their lives like many ordinary families. Striving to raise good, healthy children, endeavoring to make a living and working with the land and their other children–the cows. These are the basic human attributes that sustain and enhance life. Raising food and nurturing children. Remembering the Nelsons, I can’t help but see the stark disparities in life, lives, and livelihoods, that unfortunately continue to this day.

As I prepare my holiday meals, I am very intentional on sourcing as many ingredients as possible from local farmers to fill my table and my holiday home. I know that every dollar I spend directly with a local farmer, generates the highest value for that farmer. The food tastes the best, is clean with no worries of pathogens or errant E.coli, and keeps local lands in agriculture. The Nelsons never could sell directly to the consumer. It just wasn’t an option to sell milk and milk products in a farmstand on the side of the road or at a farmers’ market. Even now it is difficult to get locally sourced dairy products, but there are options such as Pure Eire Dairy, Grace Harbor Dairy, and Ellenos, all Washington based businesses and found at PCC Community Markets, Metropolitan Markets, and other stores that stock locally grown and processed agricultural products. I am blessed to know how important my food choices and Christmas tree decisions are to the local economy and happy to support the families that grow and nurture these products.

Kathryn Gardow, P.E., is a local food advocate, land use expert and owner of Gardow Consulting, LLC, an organization dedicated to providing multidisciplinary solutions to building sustainable communities. Kathryn has expertise in project management, planning, farmland conservation, and civil engineering, with an emphasis on creating communities that include food production. Kathryn’s blog muses on ways to create a more sustainable world and good food!

Note: The Grandma’s House & Grandpa’s Barn photo was taken by Donna Quinn and used by Gardow Consulting with permission.