Western Washington along the Interstate 5 corridor are some of the world’s most prolific farmlands. Puget Sound is blessed with a maritime climate with warm summers, cool winters, and mountain snowpacks that provide ample irrigation water through most of the growing season thus generating hefty harvests.

Despite an optimal growing climate farmers gross revenues are between 4¢ and 7¢ per square foot according to the 2012 US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Census. Whatcom County on the Canadian border has the highest agricultural revenue at 7¢ a square foot. Snohomish County, just north of Seattle and Boeing’s home with the world’s largest manufacturing building, has the lowest agricultural revenue at 4¢ per square foot. These numbers also compete with downtown Seattle Class A office space leasing at $30 per square foot. Just a basic home selling for $100 per square foot out competes the arable land value, too. Despite agricultural lands being intrinsically valuable for our health and well-being–we all do eat–the economic value of the land that grows food cannot begin to compete with development. Looking at the huge chasm between development and farm land values is one way to begin to understand why our country is losing 50 acres of farm and ranch land to development per hour, according to the American Farmland Trust. Farmland valuation versus development values is one gauge, but purchasing food is another measure to understanding why we lose farmland.

Do you know how much of each dollar you spend on food goes back to the farmer? Only 3.5¢ for every dollar spent goes back to the farmer, when eating out, whether at a restaurant or fast food joint. This number is astonishing, but not surprising when looked at more carefully. Farming is not known as a lucrative business. A farmer is better compensated with food prepared at home and gets 16¢ of every dollar spent. The USDA, through the Economic Research Services division have analyzed these numbers in their Food Dollar Series (2014).

At Home Food Dollar

2014 At Home Food Dollar

Where does our “at home food dollar” go? Almost one-quarter or 24¢ of it is spent on food processing, which is the creation of products from the raw materials. We all eat food that has been processed. Processed food staples are bread, noodles, yogurt, cheese, crackers, meats, and multiple forms of tomato products. Some products such as tomato paste have been processed a little bit, while others such as bread combine multiple ingredients. Processed foods in a grocery store, show up in the middle aisles, the freezer section, or the deli. They are in cans, boxes, bags, and jars. There are infinite opportunities to satisfy hunger with processed food! Whether the food is over-salted, has too much fat, sugar, or artificial color is another matter. I use a combination of minimally processed foods like tomato sauce and paste, and dried herbs with fresh ingredients like onions and garlic mixed in a crock-pot, to make a home cooked meal of spaghetti and meat sauce. It’s easy! The packaging of the processed food is small and only adds about 3¢ to the cost of at home food costs.

Once the food is out of the ground, processed and ready to travel to a store, this is bulk of the costs for the “at home food dollar”. Many people are involved in the effort of getting the food to us. Truckers transport food across the county or the country, wholesalers–also known as the middleman– buy raw and prepared products and sell it to retailers, grocers purchase, stock and sell food, and baggers carefully pack bags. All of these trades and more add incremental costs to food, so that in the traditional grocery store model close to half of the “at home food dollar” or 42% is spent on getting food from the farmer to you.

About 15¢ of the “at home food dollar” is spent on all the support services for the food industry around growing, processing, and selling food. The on farm inputs are called “agribusiness” and cost just over 3¢. Inputs include seed, fertilizer, farm machinery and all that is needed to grow food. Energy is almost 6¢ of the “at home food dollar” equation and covers the cost of getting the oil, gas, and coal to power the food industry. Advertising, legal services, accounting, financing and insurance are the remaining 6¢ of the “at home food dollar”.

As a consumers we are inundated with advertising on television, web pages, billboards, mailboxes, on the radio, and in magazines and newspapers. As a result of these advertisements, one would think that advertising would be a much larger slice of the food dollar, but in reality, it is just a few cents of the “at home food dollar”. Even so, it is incredible to think with the value of the total U.S. food industry at $835 billion (USDA, 2014), that the advertising slice of the “at home food dollar” is about $21 billion. These numbers put some context into the enormity of the United States food system. It’s because we all eat!

Eating Out Food Dollar

2014 Eating Out Food Dollar

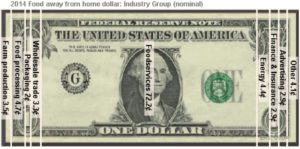

Eating food away from home supports farmers less. With almost three-quarters of the “eating out food dollar” spent on foodservice, there is not much less for anybody else including farmers. Restaurants, bars, clubs, fast-food joints and all the other venues where we buy prepared foods eat up 72¢ of the “eating out food dollar.” Food processing, packaging, wholesaling, energy, financing and insurance, advertising, and the other category including agribusiness, legal and accounting, are all a nickel or less of the “eating out food dollar”, as shown on the adjacent dollar. Farmers get a mere 3.5¢ back for every dollar spent eating out. That’s not much.

Making money as a farmer is tough. A farmer earning 3.5¢ on the “eating out food dollar” or 16¢ on the “at home food dollar,” cannot begin to earn enough money to compete with developer looking for a place to put new homes. With the average age of farmers being 59 years old and nearing retirement, it makes farmland even more vulnerable to being sold for houses.

Food Dollar Math Benefiting the Farmer

Beets at Nash’s Organic Produce Stand

Shopping at farmers’ markets is a great way for money spent on food to go directly to farmer and not to any middleman or retailer. Once a farmer’s fixed costs for seeds, fertilizers, insurance, table space at the market, labor, licenses, and transportation are covered, any revenue is his. Purchase a seasonal food delivery subscription directly from the farmer through a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. A CSA subscriber is typically asked to pay a deposit for the subscription before the season starts allowing the farmer to cover his costs for seed, fertilizer, irrigation tape, labor, and other supplies before the first CSA box is delivered. Puget Sound Fresh is a great beginning resource for the CSA search. Stop by a farm stand on the way home to support your favorite farmer. An eastern Washington farming family has just opened the Tonnemaker Woodinville Farm Stand on 14 acres. They’ll be growing western Washington produce on-site and mixing it up with their outstanding selection of eastern Washington crops like peppers, apples, pears, melons, and more! Washington grows great food and we ought to do our best to support the farmers that grow it!

Kathryn Gardow, P.E., is a local food advocate, land use expert and owner of Gardow Consulting, LLC, an organization dedicated to providing multidisciplinary solutions to building sustainable communities. Kathryn has expertise in project management, planning, fundraising, and civil engineering, with an emphasis on creating communities that include food production. Kathryn is a Washington Sustainable Food and Farming Network board member and on the Urban Land Institute–Northwest District Council’s Center for Sustainable Leadership planning team. Kathryn’s blog muses on ways to create a more sustainable world and good food!

Wonderful article, Kathryn. Thank you. I hope it is widely read.