I was born before trucking in out-of-season foods was the norm and consequently grew up eating local foods. Granted we could get iceberg lettuce and citrus shipped in mid-winter from California or Florida, but our usual nightly dinner fare was frozen beans, peas, or vegetable medley with meat and potatoes.

Corn Tassels in the Sunlight

When summer abundance arrived our dinners changed dramatically. My Dad made regular evening stops at Wade’s Farmstand** in the Connecticut River Valley before traveling over the mountain on his way home from work to purchase the freshest radishes, cucumbers, blueberries, strawberries, melons, and corn! The silken ears were freshly picked every day, because picked corn loses its sweetness with each passing hour turning the flavor to pasty starch. The strawberries burst with flavor and had to be slurped. Radishes came in rounds, spikes, as big as carrots and the colors varied from the bright red to white and every shade in between. Melon diversity ranged from smooth to rough skin with red, orange, and green inside.

Hot humid summer days, moved into crisp, clear fall days with a plethora of apple varieties, Mcouns graced the farmstand table for what always felt like a short time, while McIntosh being storage apples were available until spring. Pears, peaches, plums all thrived in the Farmington River Valley at a slightly higher elevation, upstream from its confluence with the Connecticut River.

At home, Dad also had a penchant for the ripest, most recently picked tomatoes and would grow upwards of 20 different plants, including cherries, beef steaks, early and late varieties just for the optimal burger tomato, plate of tomatoes with chives, or to just pop in the mouth. I started my first garden before I was a teenager planting Blue Lake bush beans, which continue to be my favorite.

Evolution of Seeds

Despite the wealth of food diversity I had growing up, unbeknownst to me produce choices were becoming homogenized and limited. Scientists were developing seed stock with characteristics that favored pest resistance, optimized color, generated uniform size, and insured durability for travel. Americans became busier and dependent on the grocery store, where they were trained to expect flawlessly shaped, perfectly colored, unblemished, pest-free fruits and vegetables and learned to shun the misshapen, blemished, but more flavorful produce found at the local farmstand. The seed stock changes limited produce options available at supermarkets where the customers were retrained to shop for food with their eyes, rather than with their taste buds.

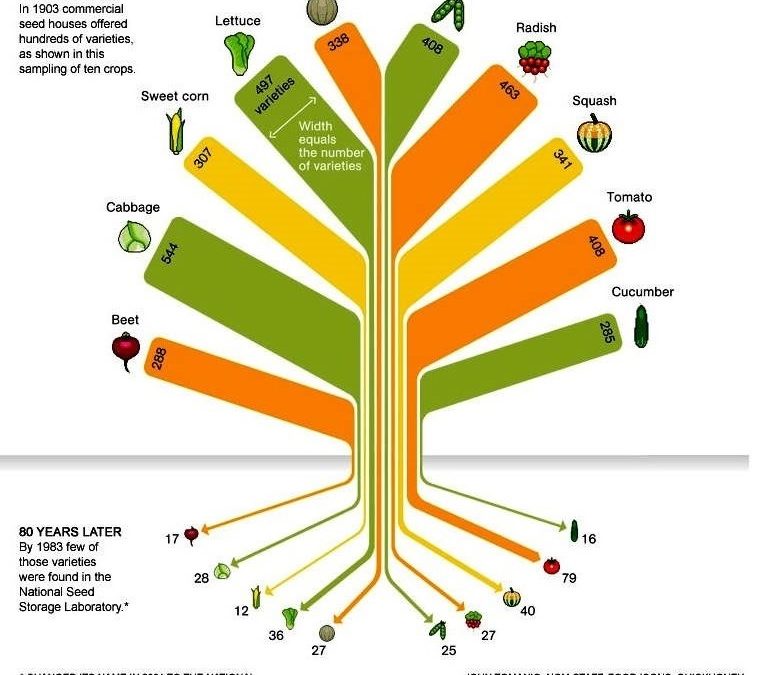

Diminution of Seed Stock over 80 years (prepared by RAFI-USA)

Produce variety loss is documented by RAFI-USA (Rural Advancement Foundation International) a non-profit that “cultivates markets, policies and communities that support thriving, socially-just, and environmentally-sound family farms,” and is depicted by the graph which illustrates the seed diversity decrease from information found at the United States’ National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation (NCGRP) [formerly known as the National Seed Storage Laboratory], located in Fort Collins, Colorado. In 1903, there were 544 different types of cabbage seed and 80 years later there were only 28, a 95% drop in seed variety. The seed selection plunged by more than 90% for all crops shown on the illustration, except for squash which fell 88% and tomato varieties which only decreased by 81%! As every high school student learns in their first biology class, diversity of a species is critical to survival and resilience. This precipitous decline in crop variety is detrimental to the sturdiness of the food system. If a weight were placed on the top of above graphic, the spindly legs of the seed stock at the bottom would collapse.

New Seed Advances

Genetically engineered (“GE”) foods, also known as genetically modified organisms (“GMO”), were first introduced for human consumption and have been expanding in the marketplace. The genetically engineered seed stock technology is revered by some, since science has engineered away pest problems by modifying plant genes. Others slander the science, since there have been no controlled studies or tests on how these genetically modified plants will impact human health or the natural environment.

Examples of GE foods are corn, soybeans, and sugar beets which have all been designed to be “RoundUp Ready,” containing a glyphosate-resistant trait and are widely grown in the United States. Glyphosate is the key ingredient in Roundup®. When it is sprayed in the fields of corn, soybeans and sugar beets it destroys the weeds and does not kill the main crop, which has been genetically modified to tolerate the Roundup® application. With American diets about 70% processed foods and the prevalence of these three crops in those foods, it is highly concerning. With 88% of the corn, 94% of the soy, and 95% of the sugar beets being genetically modified, the long-term strength of these crops is questionable, the stability of the food system is being highly compromised, and is about as sturdy as a one-legged stool. Resilience is built through diversity and the basic tenet of biology is being challenged by relying on this technology for such a large segment of the food system.

Pole Beans in my Garden

With the corn, soy and sugar beet industry essentially dominated by genetically modified crops, we are living in a time of a potential food catastrophe. If a disease, pest, fungus, superweed, or other annoying agricultural problem gets triggered, it is not unfathomable that a plant type may mutate or infect other plants. Thankfully, organic foods can not and do not include genetically engineered ingredients and are an available option for consumers. We can purchase organic foods and know we are not eating an untested science experiment.

Forward thinking eaters, are working for sustainable food systems that are “protective of the environment, economically viable, and social responsible.” Personally, I support a strong local food system and want to know where and who grows my food, to limit processed foods, to support my local farming economy, and to buy organically grown products as often as possible.

Kathryn Gardow, P.E., is a local food advocate, land use expert and owner of Gardow Consulting, an organization dedicated to providing multidisciplinary solutions to building sustainable communities. Kathryn has expertise in project management, planning, infrastructure, and civil engineering, with an emphasis on working to create communities that include food production. Kathryn’s blog muses on ways to create a more sustainable world. Gardow Consulting can also be found on Facebook.

**I am happy to see that Wade’s Farmstand is still located on Simsbury Road 95 years after its founding, as you drive west out of the Connecticut Valley with the motto, “I don’t try to sell anything in my stand that I wouldn’t want to eat myself. I’ve found that the consumer will come back to the stand only if you give him top quality.”

Note: The graphic describing the diminution of seed varieties was created by RAFI-USA. RAFI-USA does not endorse, review, or authorize the content stated on Gardow Consulting.